Setting boundaries with your phone—on your own terms

There was only one problem with my plan to write a book about my recovery from drug and alcohol addiction: my new addiction was making it impossible to get any writing done.

For several months now, I started each day with the best of intentions: meditate, eat a healthy breakfast, and sit down for two or three hours of uninterrupted writing time. But then, lunchtime would come around and I’d emerge blinking from some online rabbit hole, aghast to realize I’d spent all morning scrolling through social media or watching YouTube videos while my porridge grew cold and the page on my desk remained blank. I’d already removed every other possible distraction from my writing space: there was no TV, no radio, no sound system. I even wrote with a pen and paper, knowing I’d never be able to work on a laptop with a shimmering online world just a click away from the plain, dull Word document before me. But my smartphone—that pulsating vortex of sound and color, sleek as a silk dress, and sensitive as bare skin—well, how could I ever give it up? Even when I turned it off and stowed it away in a drawer, the thought of it sang to me like a siren. And anyway, didn’t I need to keep it close, just in case Aunt Glenys fell ill, or Martin Scorsese called to say he wanted to option my book for a film? But after another day in which all I had to show for a morning of “writing” was seventeen open browser tabs and four new Tinder matches, I saw that I’d reached a new low. It was time to take drastic measures.

When Homer’s Odysseus was due to pass the way of the sirens—sea-creatures who sang so enchantingly that no sailor could hear them without jumping overboard to his death—he had his men tie him to the mast of his ship. That way, when the sirens called to him and he longed to throw himself to the waves, he would sail safely past. Odysseus, of course, never had to contend with dating apps. Still, I figured there must be some way I could emulate his approach. How could I bind myself to the mast of my best intentions so that I could avoid drowning in a sea of online distraction? Which is how, one day a few months ago, I found myself spending $49 on a glass jar with a time-lockable plastic lid. Designed to help dieters manage their intake of sugary treats, its manufacturers promised that, once the timer was set and the cookie stash—or smartphone—was locked away, the only way to get inside would be to smash the glass. As I waited for the jar to arrive, I spent some time (on my phone, while I was supposed to be writing) reading up on internet addiction. Many experts think it’s a real, and growing, problem. In 2008, the American Journal of Psychiatry published an editorial arguing that internet addiction should be recognized as a disorder in the fifth version of the definitive text of psychiatry, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. A 2015 study of young adults found that participants were using their phones on average 85 times a day, for a total of five hours. No wonder the internet is so addictive: a Facebook Like or a Tinder match triggers a surge of dopamine in the brain. Over time, the effect on our reward system is similar to what makes a drug addict go back for another hit of crack. And the effects may be long-lasting: a study of Chinese gamers found decreases in grey matter in parts of the brain associated with cognitive function. I worried that even with the help of a time-lockable cookie jar, years of compulsive smartphone use had already eroded my ability to concentrate on anything.

On the first morning after it arrived, I set the timer for two hours. The whir and click of the mechanical lid sounded like a car’s central locking system slamming shut. First, I panicked; I felt like an astronaut in a space disaster movie who’d just lost all contact with base control. Then it struck me that before I started writing, I urgently needed to clean my entire apartment. Once I’d done that, I decided I needed to go to the stationery store. There’s only one thing worse than drifting off into outer space alone, I figured, and that’s drifting off into space without a decent stock of paper, pens, and index cards. When the two hours were up and, with relief, I was reunited with my phone, my workspace was clean and I had all the stationery I needed. But I still hadn’t done any writing. The next day, things went a little better. When the jar clicked open after two hours, I’d filled nearly a page. On the third day, feeling ambitious, I set the timer for three hours (or 180 minutes, or 10,800 seconds—not that I’d be counting), and by the end of the morning, I’d written four whole pages. But it wasn’t just that I was getting words down on paper. Before long, I realized I actually enjoyed the feeling of being disconnected from the internet for a few hours each morning. Once my mind stopped anticipating a new text message or social media interaction every five minutes, it seemed to grow calmer, and I felt more creative. The only disappointing thing was the discovery, when I turned my phone back on each day, that there were few matters in my life so urgent that they couldn’t wait two or three hours for a response.

As I write these words with my smartphone in the jar, it seems hard to believe that a decade ago hardly anybody had heard of a telephone with internet connectivity. Then, in a few short years, it became impossible to live without one—and, for some of us, they sapped so much of our attention that we felt tyrannized by them. But as I learn to use my phone more sparingly even when it’s out of the jar, I remember how wonderful smartphones seemed when they first appeared. Weirdly, I take even more pleasure in my phone than I did a few months ago—relishing the fact that it can play virtually any song ever written, or help me find my way home from anywhere in the world—instead of staring at it distractedly for hours, forgetting why I picked it up in the first place. In many ways, the cookie jar experiment has reminded me of my early forays into meditation. In the same way that sitting still and watching the breath seems to make the world more spacious and thoughts clearer, renouncing my phone each morning has made me feel like an underwater swimmer who has come up for air into a dazzling world of sound and color. Now, when I hear the jar click shut, it doesn’t sound like being locked inside a cramped and airless space. It sounds, instead, like freedom.

Be kind to your mind

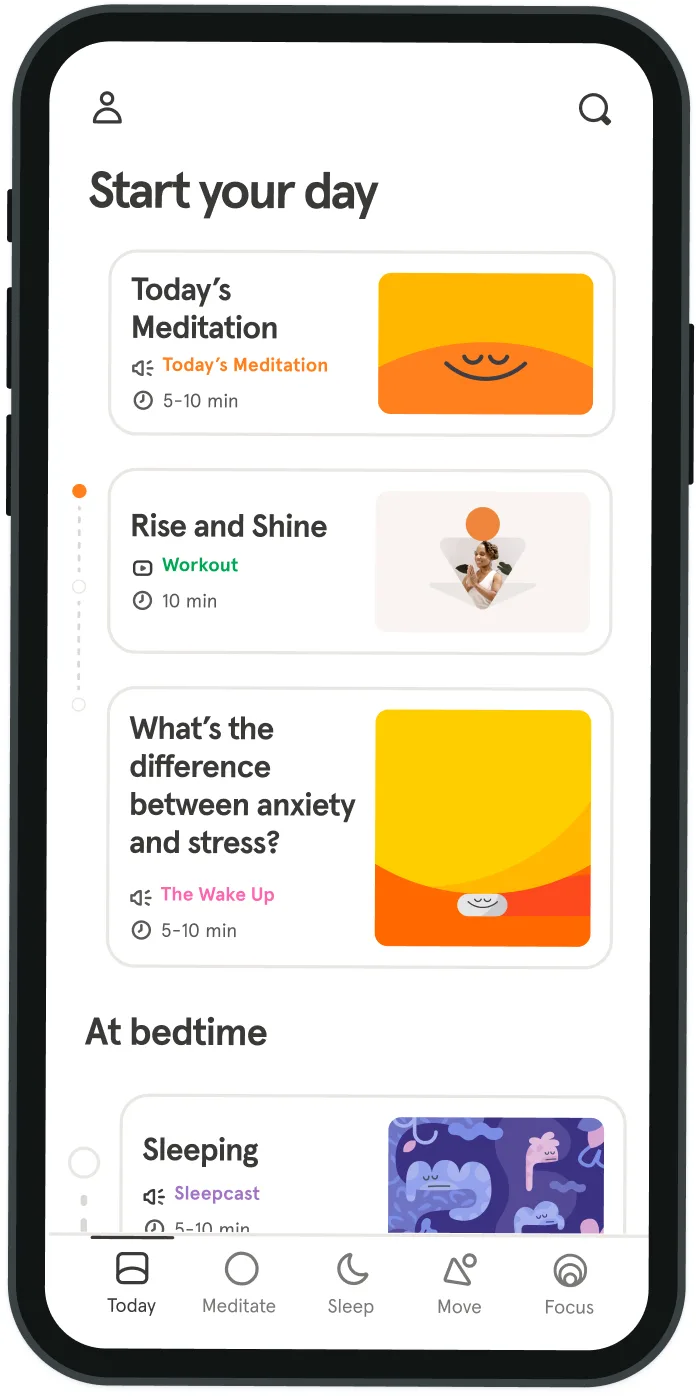

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

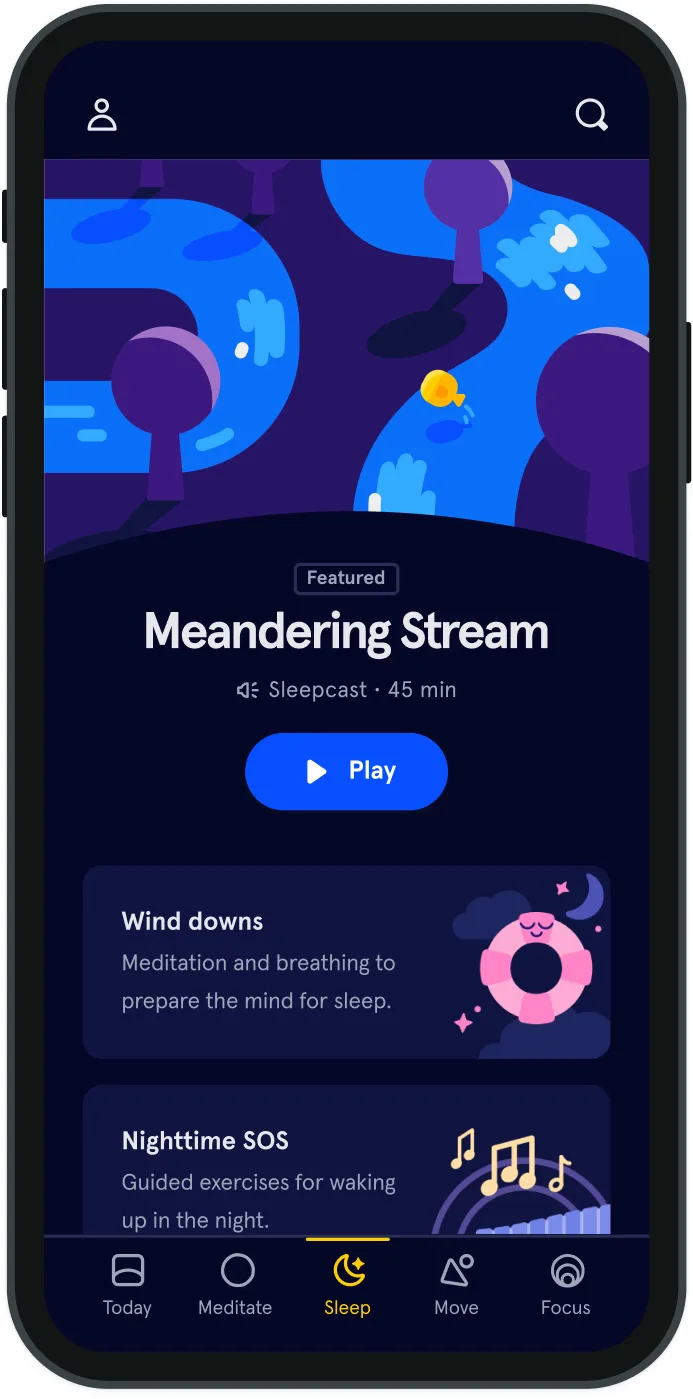

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice