The After Series: A Face in the Crowd

We spend so much of our waking lives avoiding death—in more ways than one. When it comes to talking about the inevitable, it isn’t always easy. So the Orange Dot is aiming to shine a light on these stories, in hopes that it may help others. The After Series features essays from people around the world who’ve experienced loss and want to share what comes after.

We’re transfixed, watching a stranger pump gas. My mom, dad, and I are frozen on high, animalistic alert, as we watch the young man at the neighboring gas pump. After moments that feel like years, he turns, and his face is all wrong. A five-o’clock shadow peppers his face, his cheeks are too ruddy, his eyes too far apart.

But this wasn’t possible. My brother’s body had lain in his apartment in another state for four days before being discovered. Those four days had, according to the autopsy report, turned his blue eyes brown, mottled his skin, made him bloat and blacken. Seeing what remained of him would’ve added to our trauma, decorating the dark visions in our minds with more clarity, more terrible detail than we could conjure on our own. It’s hard to believe what we can’t see. When I was pregnant, I knew abstractly that there was a baby growing inside of me. That cells were multiplying, organs and flesh being knit together, a design both miraculous and native being followed. But until the moment I saw each of my children, until I looked into their slate-gray eyes, until I felt their warm squirming legs and startled arms, some part of me didn’t really believe they were real. In the same way, without seeing my brother’s body, our minds struggled to believe he was truly dead. And so we searched. We’d spot someone in the grocery store with short sandy hair and a gray hooded sweatshirt, and we’d follow him until he turned to browse the tomato sauce section, only to see the nose and chin were all wrong. Of course it’s not Will. Will is dead, I’d think to myself, wondering if grief could actually drive a person insane. The answer was probably yes. A young man, clad in beige Carhartt coveralls, haunted the street where my dad worked. Like my brother, the boy was heavyset with thick, dark blond hair, and a similar shuffling gait. I saw him today, my dad would say grimly after work. We’d all seen him; from behind, he looked so much like my brother that I’d think, oh, there’s Will! before my brain reminded me that Will was gone.

It’s hard to believe what we can’t see. When I was pregnant, I knew abstractly that there was a baby growing inside of me. That cells were multiplying, organs and flesh being knit together, a design both miraculous and native being followed. But until the moment I saw each of my children, until I looked into their slate-gray eyes, until I felt their warm squirming legs and startled arms, some part of me didn’t really believe they were real. In the same way, without seeing my brother’s body, our minds struggled to believe he was truly dead. And so we searched. We’d spot someone in the grocery store with short sandy hair and a gray hooded sweatshirt, and we’d follow him until he turned to browse the tomato sauce section, only to see the nose and chin were all wrong. Of course it’s not Will. Will is dead, I’d think to myself, wondering if grief could actually drive a person insane. The answer was probably yes. A young man, clad in beige Carhartt coveralls, haunted the street where my dad worked. Like my brother, the boy was heavyset with thick, dark blond hair, and a similar shuffling gait. I saw him today, my dad would say grimly after work. We’d all seen him; from behind, he looked so much like my brother that I’d think, oh, there’s Will! before my brain reminded me that Will was gone. There were moments when the reality of Will’s death seeped in. Like when the hulking van pulled up in my parents’ driveway, lugging my brother’s belongings; big cardboard boxes brimming with CDs and journals, a toolbox that smelled of campfire, a small stack of letters from friends and family. As we sorted through his things, a wave of finality washed over me. He’s not coming back. He’s not just on a vacation. He’s dead.

He is not my dead brother. Not my parents’ lost son. When my brother died of a combination of drugs and alcohol three months earlier, it seemed impossible. This happens to other families, I’d thought irrationally. Though I’d suspected he’d been toying with dangerous drugs, the shock of him actually dying was acute and metallic. When possible, family members may view a loved one’s body following a death. It’s a ritual, one last chance to take in the face, the hands, the neck of someone we loved. To see the skin paled and cool, the indefinable yet palpable absence of life helps us bridge the space between our lives before the loss and the new, wrenching after. But this wasn’t possible. My brother’s body had lain in his apartment in another state for four days before being discovered. Those four days had, according to the autopsy report, turned his blue eyes brown, mottled his skin, made him bloat and blacken. Seeing what remained of him would’ve added to our trauma, decorating the dark visions in our minds with more clarity, more terrible detail than we could conjure on our own.

Or when we received his ashes, which were light and fine as sand. They both were and weren’t my brother—they were what was left of his bones after everything else burnt away. They were not, though, his skin, which was pale in the winter and golden in the summer. They were not his hair, which seemed to grow thicker the longer he went without washing it, unlike mine, which went greasy and limp between showers. They are not his hearty hands or his eyes, which, when we were kids, prompted women to bend down and ask, “Where did you get those big, blue eyes?” But mostly, time is what cemented the absoluteness of my brother’s death. Holidays and birthdays stained with his absence. Seasons that tumbled by without him. Too many strangers in the grocery store, on the sidewalk, at the airport, turning to reveal their wrong faces. It’s been 18 years now since my brother died. I don’t search for him anymore—his goneness, spread over so much time, has etched the truth into me. I don’t double-take at gas stations or grocery stores. If Will were still alive, he’d be nearly 40. I can’t imagine my brother at 40, almost twice the age he was when I last saw him. I can’t envision what type of clothes he’d wear, whether any gray hairs would sprout on his temples, whether he’d be slender or thick-waisted. What his children—my ghost-nieces or nephews—might look like. I can’t see any of it, and so I don’t look. But I still see him. In my son whose eyes are strikingly similar to Will’s. And sometimes, in deep, syrupy dreams, he’s resurrected. Young and lovely, whole and here.

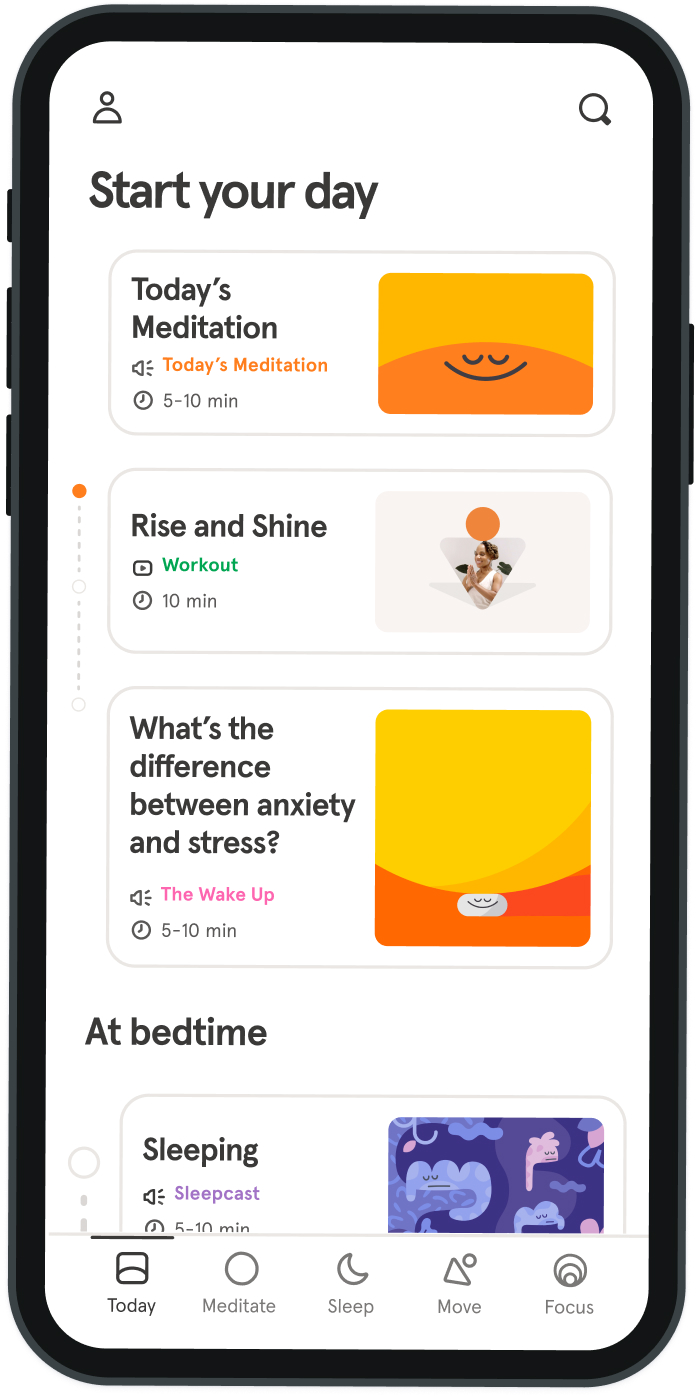

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice