Cheat meals, guilty pleasures, and our complex relationships with food

"Cheat meal!" "Guilty pleasure!"

Scroll through food photos on Instagram and these words leap out. At a gym on a Monday, you can hear people obsessing about what they ate over the weekend—not truckloads, but a piece of bread, a cupcake. And I’ve often chimed in: “I ate two naans last night!” Why do we feel this compulsive need to confess? More importantly, what do we feel guilty about? Our guilt draws from historical perceptions of gourmands, the idea of gluttony, and popular food culture. Popular food culture stokes this with descriptors like ‘indulgence’, ‘sinful’ and ‘treats.’ And so basic nourishment is now imbued with as much guilt as an actual crime. As the food writer Bee Wilson notes in her book "First Bite", religious guilt has shifted from our private lives to eating. “Like hypocritical temperance preachers, we demonize many of the things we consume most avidly, leaving us at odds with our own appetites,” Wilson writes.

It took me a while to realize I’d internalized these feelings. I’ve almost always felt or been overweight—ten pounds too heavy. While growing up in Pakistan, I was conscious that I had a different body structure. I had wide hips and breasts and a round face. Girls like me were dubbed ‘moti’—fat—or derisively called ‘healthy’. I knew I was never going to match the conventional idea of being thin. But in my late teens, I felt I didn’t look good. A yoga teacher spurred me to give up soda and chocolate-rich desserts. Among Pakistani women, mangoes are often seen as kryptonite. The delicious, succulent fruit is described as “equal to four pieces of bread” or other scaremongering numbers. Even as I mocked this, I stopped eating mangoes. Freshly roasted nuts—which I’d eat by the handful on winter evenings—were worse, according to common lore, because they apparently caused weight gain and acne. I divided food into camps: “good” and “bad”. Anything delicious was “bad” by default, like parathas, the crispy flatbread I love. When I ate something “bad”, I felt horrible about myself. Even after I started working out regularly, I felt I needed to do more. I started a cereal-based diet after seeing ads for Kelloggs’ Special K cereal on TV that mentioned you could lose weight on a cereal-eating challenge. While I felt virtuous with each bowl, that quickly shifted to resentment when I ate anything else (out of sheer hunger.) I lucked out with a Ketogenic diet that helped me get over my assumptions about fat and portion sizes. But I’d spend days beating myself up for ‘transgressions’. If only I hadn’t eaten that piece of cake, I’d fit into this shirt; if I only eat fat for two days, I’ll be thin. I felt like a “bad” person whose punishment was extra pounds.

“Dieting generally makes people's mood more negative on a daily basis, and calorie restriction has been shown to lead to a physiological stress response,” says psychologist Dr. Traci Mann, author of "Secrets from the Eating Lab". “Forbidding people from eating specific foods leads them to think about and desire those foods more. If they fail to stick to their rule forbidding those foods, they may feel guilt specifically about this failure, or shame—a more global negative feeling about oneself.” I cried constantly. I’d sacrificed so much—giving up rice, bread, mangoes—and gained little. Last year, I talked this through on the Summer Tomato podcast hosted by Dr. Darya Rose, the author of "Foodist". As I finally vocalized my issues, it became clear that moralizing and guilt weren’t helping my relationship with food. Dr. Rose’s advice helped me see that I could eat well, re-introduce foods, and start changing the way I perceived eating. She advocates an approach of building habits that help one’s long-term health, like incorporating foods in your meals that are delicious, good for your health, and that you enjoy, or using a fitness tracker to set yourself a goal of steps walked every day. It is difficult. When I peruse a menu, I still often look for what would be “better”, not more delicious. But this is what we need to change. “Individuals need to make an effort to view their food choices with a more neutral eye, rather than as a moral choice,” says Dr. Mann. “I recommend that people don't forbid themselves from eating certain foods, or certain categories of foods, but rather aim to eat a large variety of different foods, and in sensible quantities. Once you forbid a food, you want it more, so it just backfires.” Sometimes I regret how long it took me to cut away at this guilt—and the mangoes I missed out on. But I am thankful every time I enjoy cake without wondering if this makes me a good person. And that’s a good place to be.

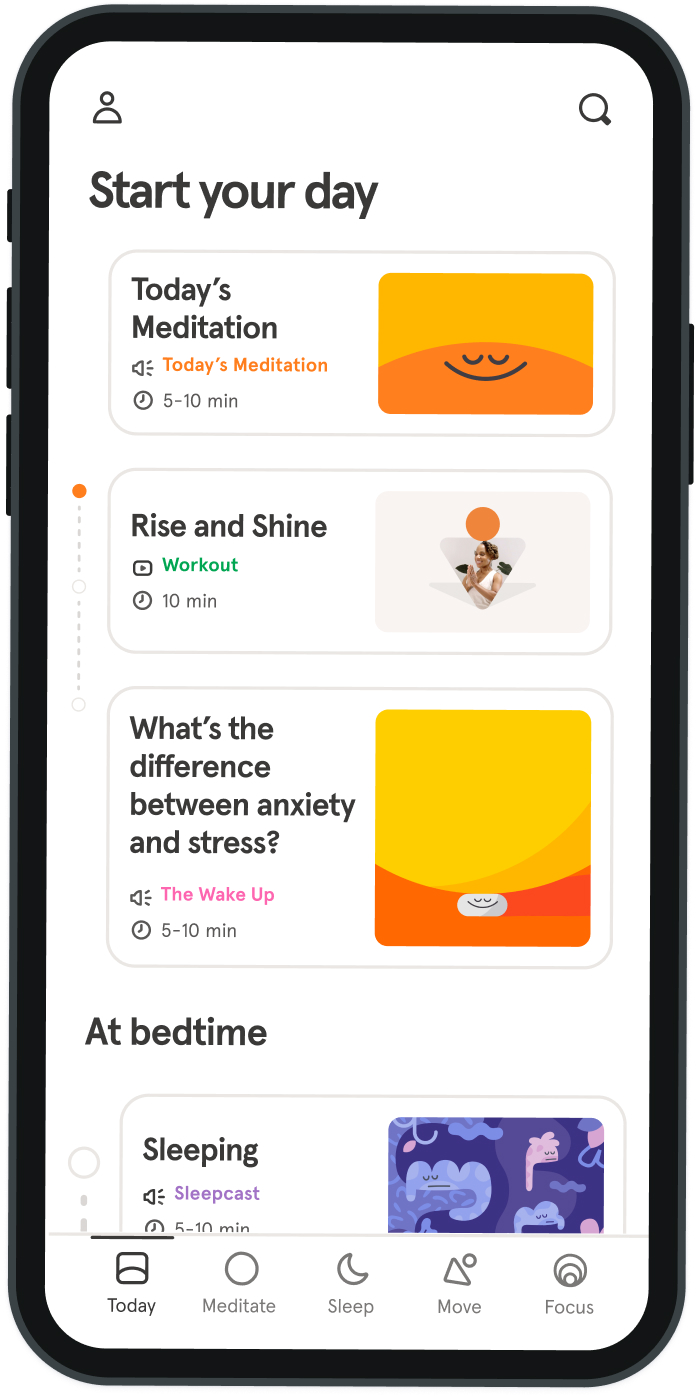

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice