New emojis have arrived, but should we use them?

Start your free trialQuite apart from the accessibility issues (think about navigating emojis as a blind, or even color blind, internet user), emoji-speak contributes to a generational disorientation with an internet culture in which images are rapidly overtaking words. Those of us who grew up on printed software manuals that could double as doorstops have struggled with a new wave of software tools that are documented only through how-to videos. Where people once shared newspaper clippings, we now circulate 2-minute video clips. And Snapchat guides for the baffled over-30 set are proliferating so rapidly that they’ll soon qualify as their own literary genre. I recognize that for many people, visual communication is more intuitive than text. For these visual learners and thinkers, the shift towards a visual communication culture makes relationship, learning and connection much easier, and enriches their interactions in ways that text alone cannot satisfy. To them, I say

Emoji-speak contributes to a generational disorientation with an internet culture in which images are rapidly overtaking words.

Alexandra Samuel

Emoji-speak contributes to a generational disorientation with an internet culture in which images are rapidly overtaking words.

Alexandra Samuel

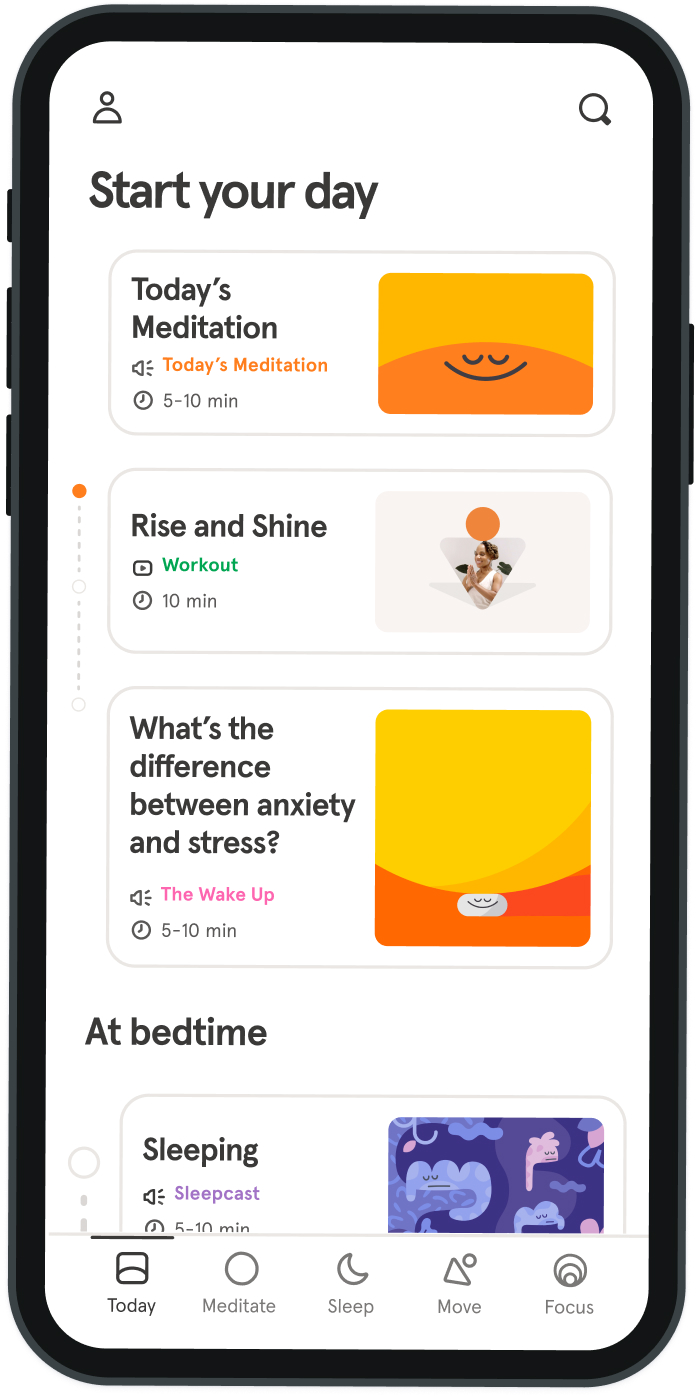

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

Stay in the loop

Be the first to get updates on our latest content, special offers, and new features.

By signing up, you’re agreeing to receive marketing emails from Headspace. You can unsubscribe at any time. For more details, check out our Privacy Policy.

- © 2025 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice