Sometimes, facts don’t seem to matter. Here’s why.

A woman I knew years ago in high school turns up often in my Facebook feed. When her posts show up, my body tenses and I become irritated. Sometimes, she posts a cute photo of her kids or a funny anecdote from the morning. But, often, it’s an attack on a political movement I believe in or a sweeping generalization about a particular demographic.

When I see these posts, a few thoughts run through my mind—“how could she be so stupid?” and “who could possibly believe this garbage?” (I don’t approach her sources with a terribly open mind.) This isn’t something I face with most people in my social media networks. Mostly, the people who post about politics are more or less in line with my thinking. When I see the sources they link to, my eyes glide easily over them; I quietly file away a new scrap of information about the environment or agricultural practices. I suffer from confirmation bias. You probably do, too. A wide range of studies over more than half a century has found that people tend to accept information that’s in line with what we already believe and reject evidence that contradicts our preconceptions. But in a world where people are increasingly retreating into curated bubbles of like-minded people, it’s worth learning more about these tendencies.

In the 1960s, British psychologist Peter Wason conducted an experiment demonstrating confirmation bias. He told subjects he had a rule in mind governing a set of three numbers. For example 2-4-6. Then, he asked them to guess the rule and suggest other sets of numbers to see if they fit. Most participants made suggestions like 8-10-12 and 20-22-24. After being told that these did fit the pattern, most concluded that Wason was looking for a series of even numbers increasing by two. What most people didn’t do was test sequences like 1-3-5 or 4-7-21. If they’d done that, they might have realized that the actual rule was simply that each number was higher than the last. This failure to reckon with evidence that might contradict an initial hypothesis takes on a more complex form when applied to more high-stakes subjects. In 2013, a team of researchers asked people to analyze a tricky set of data about the effects of a new skin rash treatment. Not surprisingly, those skilled at math tended to do best. But when researchers told subjects that the same data related to a stance on gun control, math skills no longer predicted an accurate analysis. Instead, the political outlooks of the subjects mattered. In fact, people who were mathematically skilled were especially likely to answer incorrectly if the data disagreed with their preconceptions. The authors concluded that these subjects used their “quantitative-reasoning capacity selectively to conform their interpretation of the data to the result most consistent with their political outlooks.” If cleverness won’t save us from our biases, what can? How can you notice your own preconceptions, take in information that contradicts your current beliefs, and have productive discussions with people you disagree with? Here’s how experts weigh in: 1. Have some humility. Myer J. Sankary is a Los Angeles-based lawyer and mediator who trains lawyers in addressing bias. According to him, it can be difficult for some to accept those from different backgrounds as our intellectual equals. “That’s the hard part, recognizing the humanity of others,” he adds. “You’re not so knowledgeable, and you’re not so perfect, and other people have a lot to contribute.”

2. Don’t be too trusting. We’re rarely skeptical of the people we often agree with—but it’s a good habit to practice. When psychologists replicated Wason’s 2-4-6 experiment in 2013, they found they could change subjects’ responses simply by showing them a picture of a “distrust-inducing” face with narrowed eyes. Those who saw that picture were more likely to be cautious about reaching an easy conclusion and more likely to test at least one set of numbers that didn’t fit with an initial hypothesis. 3. Engage with people you kind of disagree with. Julia Galef, a writer and speaker who focuses on strategies for rational thinking, recently noted that many people believe they should engage with people who are their polar opposites. “I think that doesn’t work that well, partly because you just don’t have a lot of shared premises to argue from, but also because emotionally, someone who’s 180 degrees away from you is probably going to annoy you,” she said. “It’s going to make it really hard for you to be genuinely curious about why they believe something so differently than you.” 4. Challenge your own thought process. In a 1985 experiment, researchers encouraged people who were for or against the death penalty to read evidence about the issue. They found that reading studies supporting their existing position strengthened subjects’ resolve—but, so did contradictory evidence. Even when advised to try to be as objective as possible, most people distrusted studies that disagreed with their premises. But when researchers asked subjects to pause frequently and consider what they would have thought if "exactly the same study produced results on the other side of the issue,” they found people took the new evidence seriously. They didn’t generally change their opinion, but they now found the “disagreeable” studies as credible as the ones they agreed with. One thing you might notice about resisting cognitive bias is that it takes practice, time, and mental energy to look at things in a different way and challenge your existing beliefs. Equally, it’s also not always necessary. There’s no need to form an opinion about every article on Facebook. But if I want to have an honest conversation, I ought to spend the time and energy required to pause and question my own assumptions.

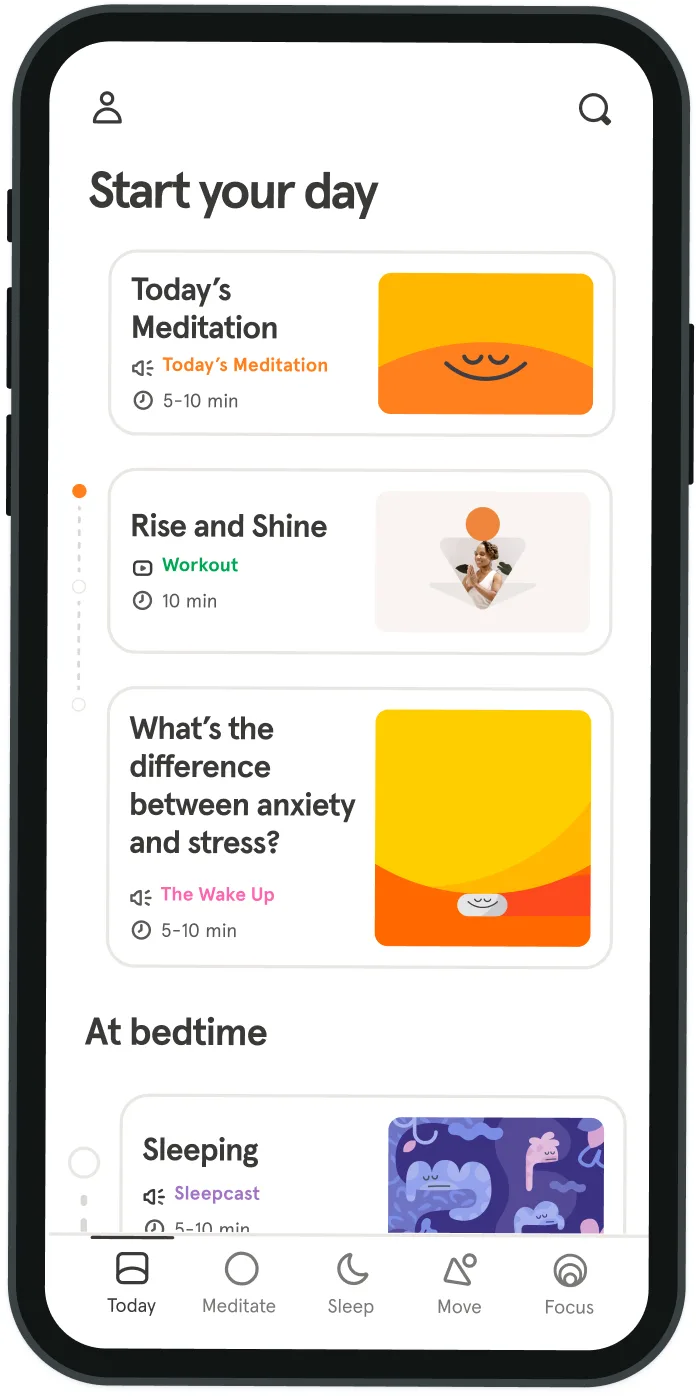

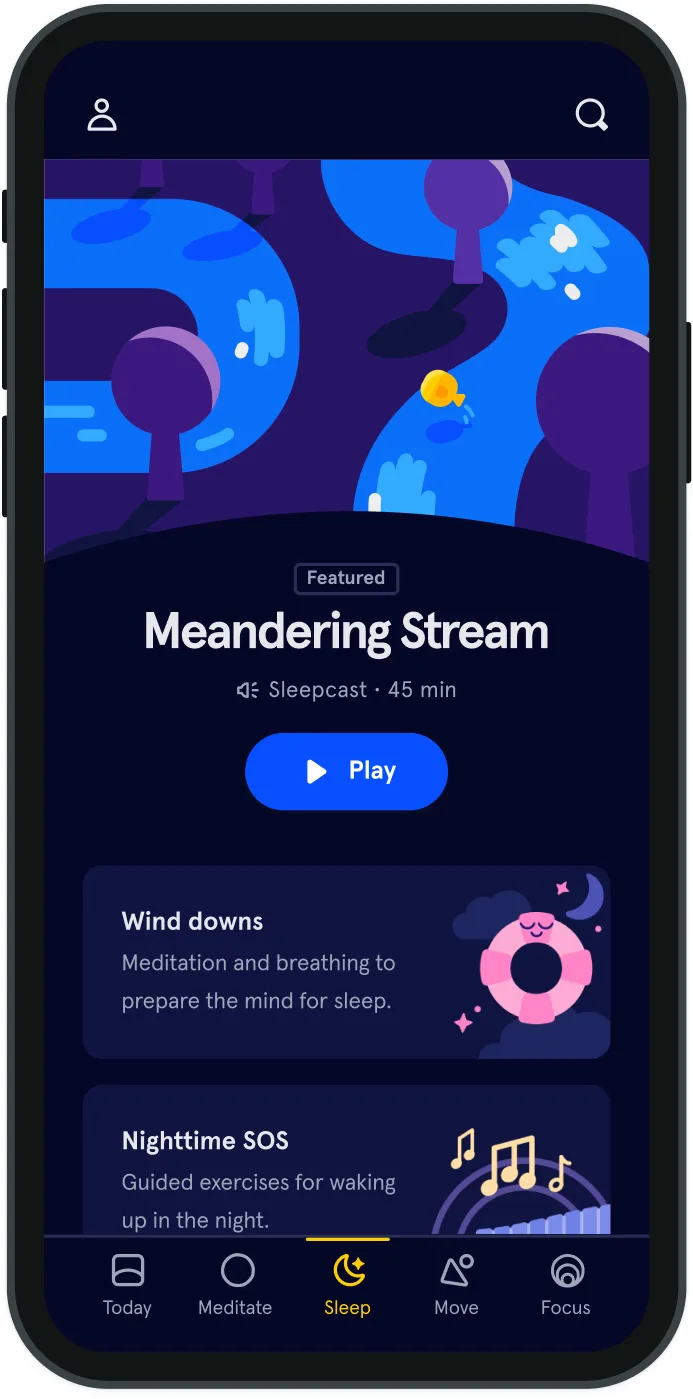

Be kind to your mind

- Access the full library of 500+ meditations on everything from stress, to resilience, to compassion

- Put your mind to bed with sleep sounds, music, and wind-down exercises

- Make mindfulness a part of your daily routine with tension-releasing workouts, relaxing yoga, Focus music playlists, and more

Meditation and mindfulness for any mind, any mood, any goal

- © 2024 Headspace Inc.

- Terms & conditions

- Privacy policy

- Consumer Health Data

- Your privacy choices

- CA Privacy Notice